Abstract

Transparent Reporting of Observational Studies Emulating a Target Trial: The TARGET Guideline

Aidan G. Cashin,1,2 Harrison J. Hansford,1,2 Miguel A. Hernán,3,4,5 Sonja A. Swanson,3,4,6 Hopin Lee,7,8 Matthew D. Jones,1,2 Issa J. Dahabreh,3,4,5,9 Barbra A. Dickerman,3,4 Matthias Egger,10,11,12 Xabier Garcia-Albeniz,3,13 Robert M. Golub,14 Nazrul Islam,15,16 Sara Lodi,3,17 Margarita Moreno-Betancur,18,19 Sallie-Anne Pearson,20 Sebastian Schneeweiss,21 Melissa K. Sharp,22 Jonathan A. C. Sterne,12,23,24 Elizabeth A. Stuart,25 James H. McAuley1,2

Objective

When randomized trials are unavailable or not feasible, data from observational studies can be used, if assumptions hold, to answer causal questions about the comparative effects of interventions by emulating a hypothetical pragmatic randomized trial (target trial). The reporting of studies that emulate a target trial is inconsistent and often incomplete, limiting transparency and reproducibility. To address this knowledge gap, we developed consensus-based guidance for reporting analyses of observational data that aim to estimate causal effects by explicitly emulating a target trial.

Design

The TARGET (Transparent Reporting of Observational Studies Emulating a Target Trial)1 guideline was developed using the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) framework.2 This included (1) a systematic review3 of reporting practices in published studies that explicitly aimed to emulate a target trial, (2) a 2-round online survey (August 2023-March 2024; 18 expert participants from 6 countries) to generate agreement on the importance of candidate items selected from previous research and to identify additional items, (3) a 3-day expert consensus meeting (June 2024; 18 panelists) to refine the scope of the guideline and draft the checklist, and (4) an internal and external review and piloting activity with stakeholders and potential users (n = 108; September 2024-February 2025). The checklist was then refined based on feedback and finalized.

Results

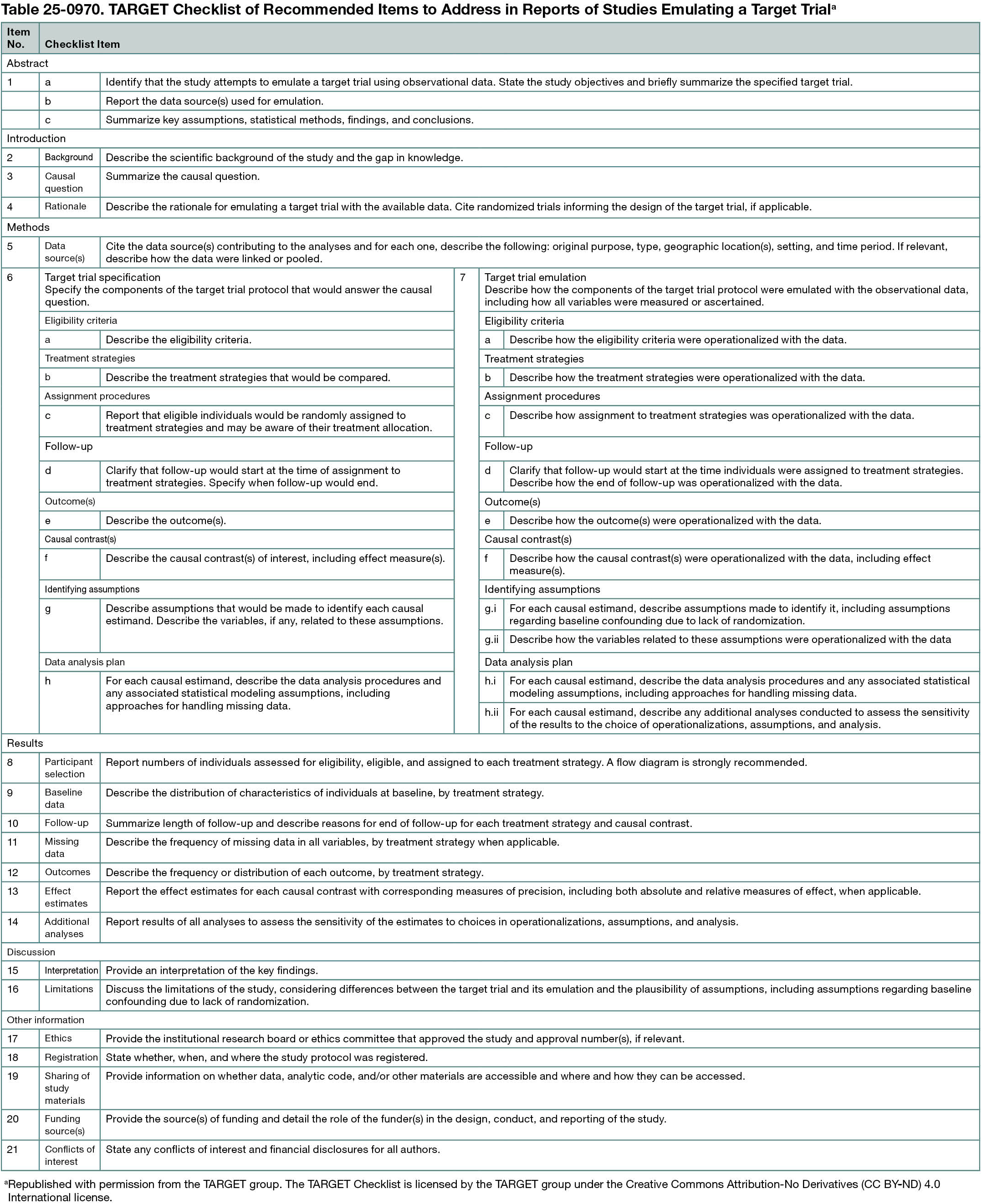

The 21-item TARGET checklist was organized into 6 sections (abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, other information) (Table 25-0970). The TARGET guideline was intended to be general, with a focus on nonrandomized studies of interventions explicitly emulating a parallel-group, individually randomized target trial, with adjustment for baseline confounders. Key recommendations were to (1) summarize the causal question and the reason for emulating a target trial; (2) clearly specify the target trial protocol (ie, causal estimand, identifying assumptions, data analysis plan) and how these components were mapped to the observational data; and (3) for each causal estimand, report the estimate obtained and its precision, along with findings from additional analyses to assess the sensitivity of estimates to assumptions and design and analysis choices.

Conclusions

The TARGET guideline provides recommendations on reporting of studies explicitly emulating a target trial. Use of the guideline should facilitate transparency in reporting to improve peer review and help researchers, clinicians, and other readers interpret and use the results.

References

1. Hansford HJ, Cashin AG, Jones MD, et al. Development of the TrAnsparent ReportinG of observational studies Emulating a Target trial (TARGET) guideline. BMJ Open. 2023;13(9):e074626. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074626

2. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000217. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217

3. Hansford HJ, Cashin AG, Jones MD, et al. Reporting of observational studies explicitly aiming to emulate randomized trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(9):e2336023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.36023

1School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine & Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, a.cashin.neura.edu.au; 2Centre for Pain IMPACT, Neuroscience Research Australia, Sydney, Australia; 3CAUSALab, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, US; 4Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, US; 5Department of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, US; 6Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, US; 7University of Exeter Medical School, Exeter, UK; 8IQVIA, London, UK; 9Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, US; 10Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; 11Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Research, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; 12Department of Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; 13RTI Health Solutions, Barcelona, Spain; 14Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, US; 15Oxford Population Health, Big Data Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; 16Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK; 17Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, US; 18Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics Unit, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 19Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia; 20School of Population Health, Faculty of Medicine & Health, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia; 21Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, US; 22Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, School of Population Health, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin, Ireland; 23NIHR Bristol Biomedical Research Centre, Bristol, UK; 24Health Data Research UK South-West, Bristol, UK; 25Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, US.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Miguel A. Hernán is an advisor to ProPublica and Adigens Health, in which he owns equity, and a member of ADIA Lab’s advisory board. Issa J. Dahabreh is a consultant to Moderna on work related to target trial emulation. Sebastian Schneeweiss is participating in investigator-initiated grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, and UCB unrelated to the topic of this study; is an advisor to and owns equity in Aetion, a software manufacturer; and is an advisor to Temedica, a patient-oriented data generation company.

Funding/Support

This work received no direct funding. The TARGET consensus meeting was supported through proceeds from a course on causal inference (December 4-7, 2023; Sydney, Australia). Aidan G. Cashin was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grant (2010088). Harrison J. Hansford was supported by an Australian NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (2021950), a PhD Top-Up Scholarship from Neuroscience Research Australia, and was a Neuroscience Research Australia PhD Pearl sponsored by Sandra Salteri, AO. Miguel A. Hernán was funded by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant (R37 AI102634). Issa J. Dahabreh was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award (ME-2021C2-22365) and an NIH award (R01HL136708). Barbra A. Dickerman was supported by a grant from the NIH (R00 CA248335). Matthias Egger was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 AI152772-01, 5U01-AI069924-05) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (32FP30-174281). Nazrul Islam was supported by grants from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR; HDRUK2022.0313) and the UK Office for National Statistics (2002563). Margarita Moreno-Betancur was supported by an Australian NHMRC Investigator Grant (2009572). Sebastian Schneeweiss was supported by the NIH (R01-HL141505, R01-AR080194) and the US Food and Drug Administration (HHSF223201710146C). Jonathan A. C. Sterne was supported by the NIHR Bristol Biomedical Research Centre and by Health Data Research UK. Elizabeth A. Stuart was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 MH126856) and PCORI (ME-2020C3-21145). James H. McAuley was supported by an Australian NHMRC Investigator Grant (2010128).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation review, or approval of the abstract; and decision to submit the abstract for publication.

Additional Information

Aidan G. Cashin and Harrison J. Hansford are co–first authors.

Acknowledgment

We thank and acknowledge the contributions of all participants of the internal and external piloting who were not compensated for their contributions.