Abstract

Assessment of Spin Among Diagnostic Accuracy Meta-Analyses Published in Top Pathology Journals: A Systematic Review

Griffin Hughes,1 Andrew Tran,1 Sydney Marouk,1 Eli Paul,1 Matt Vassar1,2

Objective

The overinterpretation of research findings—otherwise known as “spin”—is commonly assessed in clinical trials and synthesis designs of interventional evidence.1,2 However, spin in diagnostic evidence has received less attention and has fewer published works.3 Therefore, we conducted a systematic review aimed to assess spin in pathology’s diagnostic accuracy meta-analyses.

Design

Using systematic review methodology, we searched PubMed (MEDLINE) on September 21, 2023, for diagnostic test accuracy meta-analyses published in top 20 pathology journals. To be included for data extraction, studies must have (1) been a systematic review with meta-analysis of primary studies identified through a literature search, (2) pooled diagnostic accuracy effects for a quantitative summary effect estimation, and (3) been published in a top 20 pathology journal, defined by Google Scholar Metrics’ h5-index. We excluded studies that (1) did not represent systematic reviews with meta-analyses; (2) did not quantitatively pool diagnostic accuracy measures; (3) were primarily prognostic in their aims; (4) were published before the publication of the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies quality tool; or (5) represented publication types such as erratum, retractions, or corrigendum. We derived 10 items of actual spin and 9 items of potential spin from previously published methodology assessing overinterpretation of results in quantitative diagnostic synthesis.3 Studies with conclusions interpreted as positive were assessed for actual spin, whereas all studies were assessed for potential spin. Authors screened and extracted relevant data from sample studies in a masked duplicate fashion to reduce extraction errors. A third author was available to resolve discrepancies. We conducted descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, using R in RStudio.

Results

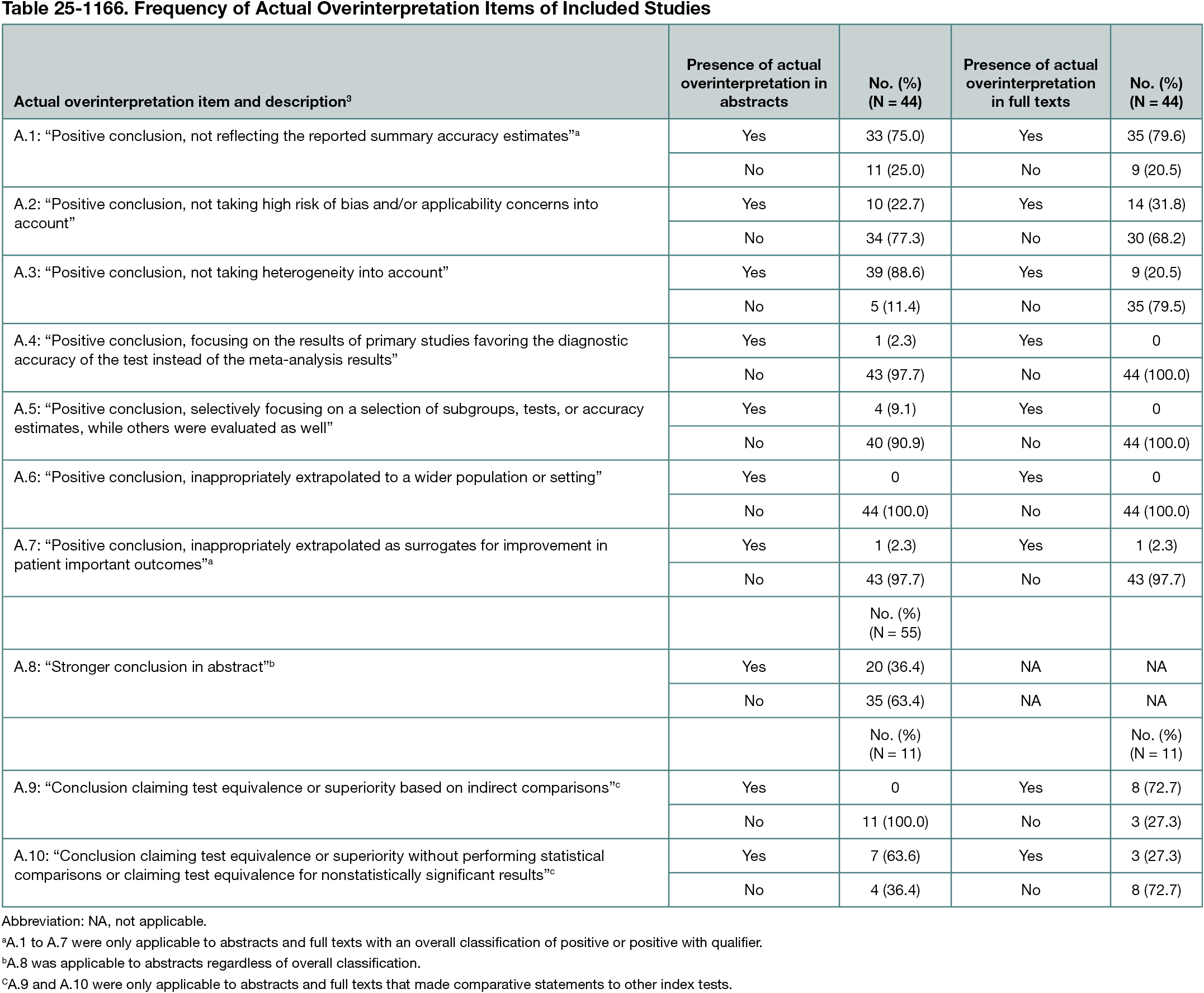

We identified 207 articles from PubMed for potential inclusion. After screening, 55 abstracts and full texts were available for full data extraction, with 80% (44 of 55) having positive conclusions germane to accuracy or clinical implications. At least 1 item of spin was present in every included article. Most positive conclusions in abstracts (75% [33 of 44]) and full texts (79.6% [35 of 44]) did not adequately reflect pooled estimates (Table 25-1166). A total of 34.5% of studies (19 of 55) used nonrecommended statistical approaches for pooling accuracy measures, reflecting potential spin. All 55 studies reported CIs within their full text for precision interpretation.

Conclusions

Diagnostic test accuracy meta-analyses published within the top 20 pathology journals consistently overinterpret their findings. Authors should ensure that their findings are properly contextualized within predetermined diagnostic performance criteria. Additionally, authors should ensure that summary estimates are pooled using appropriate and robust methods that maintain the correlated nature of sensitivity and specificity.

References

1. Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2058-2064. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.651

2. Yavchitz A, Ravaud P, Altman DG, et al. A new classification of spin in systematic reviews and meta-analyses was developed and ranked according to the severity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:56-65. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.020

3. McGrath TA, Bowdridge JC, Prager R, et al. Overinterpretation of research findings: evaluation of “spin” in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy studies in high-impact factor journals. Clin Chem. 2020;66(7):915-924. doi:10.1093/clinchem/hvaa093

1Office of Medical Student Research, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Tulsa, OK, US, griffinhughesresearch@gmail.com; 2Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, Tulsa, OK, US.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Matt Vassar receives funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the US Office of Research Integrity, Oklahoma Center for Advancement of Science & Technology, and internal grants from Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences outside the present work. All other authors have nothing to disclose.