Analysis of Decisions and Lead-Time in Ethical Review Boards in Sweden

Abstract

Emmanuel A. Zavalis,1 Love Ahnström,2 Natasha Olsson,2 Gustav Nilsonne2,3

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess lead times and application decisions using the national database of the Swedish Ethical Review Authority since its inception. We also aimed to assess the effect of the COVID-19 ethical review fast-track implemented in spring 2020. Prior studies of ethical review have been limited to single or few institutions.1,2

Design

This retrospective analysis examined 21,962 administrative records of all ethical review applications submitted in Sweden between 2021 and 2023. The applications were categorized by type (eg, amendments, clinical trial, or processing sensitive data) and sponsor (eg, health care systems, universities, or corporations). Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed for analysis of time to decision. Adherence to statutory deadlines was assessed for amendments (35 days) and drug trials (60 days).3 Log-rank test was used for statistical testing with α = .05 as a significance threshold.

Results

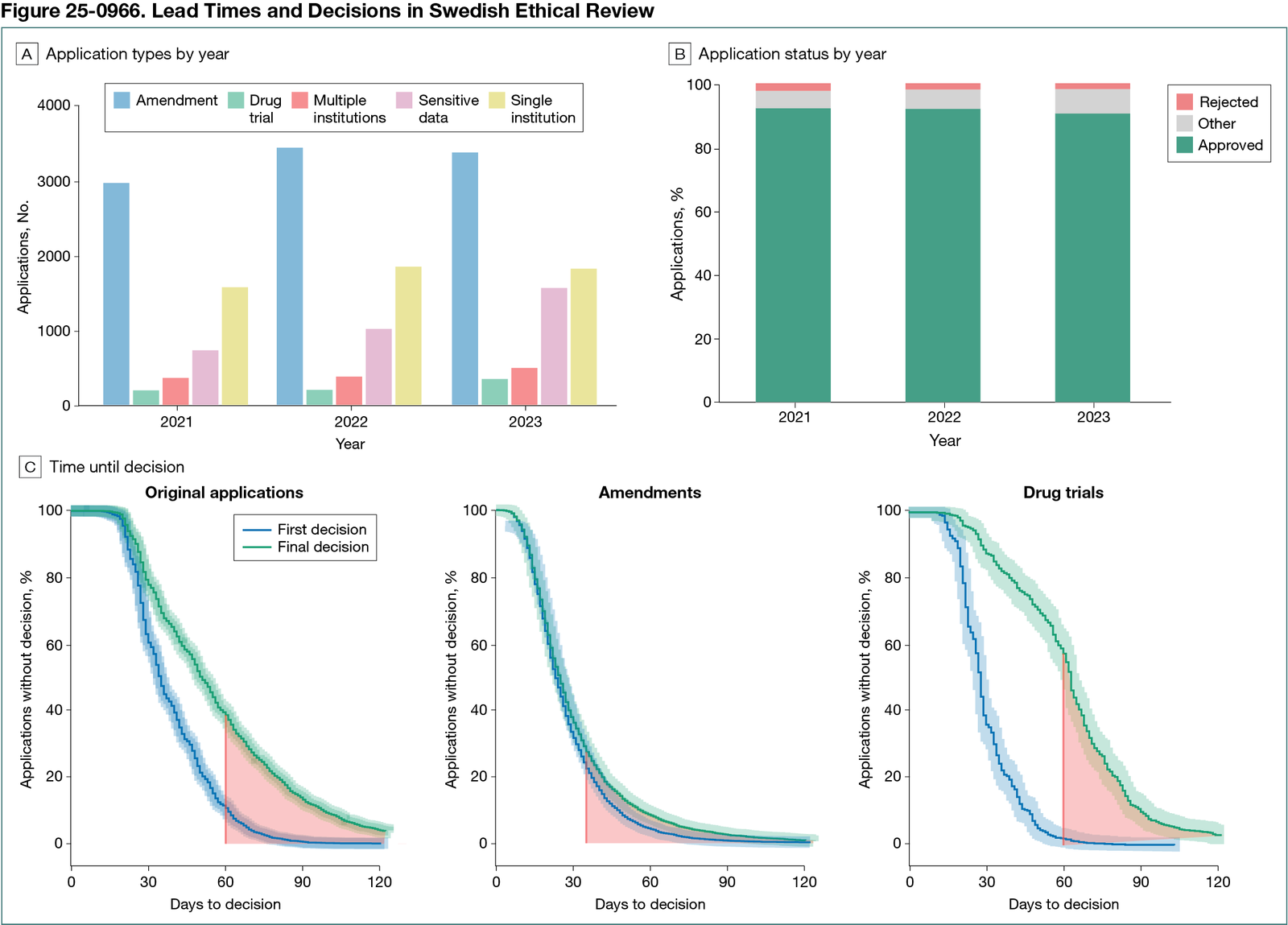

Following exclusions (eg, incomplete applications, unpaid fees, or withdrawals), 20,440 applications remained: 5866 from 2021, 6926 from 2022, and 7648 from 2023. Submissions were primarily from health care systems (10,456 [51%]) and universities (8681 [42%]), with corporations accounting for 578 applications (3%). Amendment applications constituted the largest category of applications (51% in 2021, 50% in 2022, and 44% in 2023). Applications in the “processing of personal data” category doubled from 736 to 1574 over the study period (Figure 25-0966, A). Of the 20,440 applications, initial approvals accounted for 68% (n = 13,864), further information or change to the project was requested in 24% (n = 5001) of cases, and 1.5% (n = 313) were rejected. Final decisions resulted in approvals for 91% (n = 18,516), with rejections being rare (2%), as seen in Figure 25-0966, B. Geographic variation was observed, with Stockholm having the shortest (34 days) and Lund the longest (43 days) median lead times. COVID-19 studies were associated with expedited processing times (median time to decision, 51 vs 63 days; P < .001). While 27% of amendment applications were without a decision after 35 days, 39% of original applications as well as 58% of drug trials were without a decision after 60 days (Figure 25-0966, C).

Conclusions

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority mainly handled amendments. Lead times were longer than statutory deadlines for more than half of drug trials and for a quarter of amendments. The processing times showed geographic variations, and the fast-track for COVID-19 showed a significant association with processing times. Further studies of the qualitative aspects of ethical reviews’ impact on research plans as well as the nature of the applications for amendments would be of interest for a better understanding of the value introduced and the harms prevented by ethical review.

References

1. Hall DE, Hanusa BH, Stone RA, Ling BS, Arnold RM. Time required for institutional review board review at one Veterans Affairs medical center. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(2):103. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2014.956

2. Varley PR, Feske U, Gao S, et al. Time required to review research protocols at 10 Veterans Affairs institutional review boards. J Surg Res. 2016;204(2):481-489. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.004

3. Sveriges Riksdag. Ordinance (2003:615) on ethical review of research involving humans. Accessed January 18, 2025. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/forordning-2003615-om-etikprovning-av-forskning_sfs-2003-615/

1Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 2Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, gustav.nilsonne@ki.se; 3Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None reported.