Abstract

Impact of FDAAA on Registration, Results Reporting, and Publication of Neuropsychiatric Clinical Trials Supporting FDA New Drug Approval, 2005-2014

Constance X. Zou,1 Jessica E. Becker,2,3,4 Adam T. Phillips,5 Harlan M. Krumholz,6,7,8,9 Jennifer E. Miller,10 Joseph S. Ross7,8,9

Objective

Selective publication and reporting of clinical trial results undermines evidence-based medicine. The 2007 Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) mandates, with few exceptions, the registration and reporting of results of all non–phase I clinical trials on ClinicalTrials.gov for approved products. The objective of this study was to determine whether efficacy trials supporting US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of new drugs used for neurological and psychiatric conditions that were completed after FDAAA was enacted were more likely to have been registered, have their results reported, and be published in journals than those completed pre-FDAAA.

Design

We conducted a retrospective observational study of efficacy trials reviewed by the FDA as part of any new neuropsychiatric drugs approved between 2005 and 2014. In January 2017, for each trial, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for the registration record and for reported results, and we searched MEDLINE-indexed journals using PubMed for corresponding publications. In addition, published findings were validated against FDA interpretations described in regulatory medical review documents. Trials were considered FDAAA applicable if they were initiated after September 27, 2007, or were still ongoing as of December 26, 2007. The rates of trial registration, results reporting, publication, and publication-FDA agreement were compared between pre-FDAAA and post-FDAAA trials using Fisher exact test.

Results

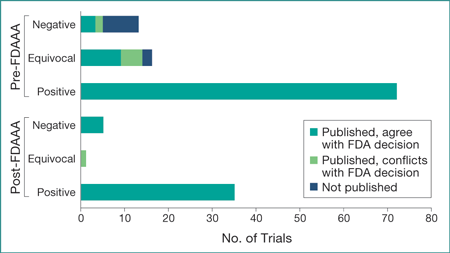

Between 2005 and 2014, the FDA approved 37 new neuropsychiatric drugs on the basis of 142 efficacy trials, of which 41 were FDAAA applicable. Post-FDAAA trials were significantly more likely to be registered (100% vs 64%; P < .001) and to report results (100% vs 10%; P < .001) than pre-FDAAA trials, but post-FDAAA trials were not significantly more likely to have been published (100% vs 90%; P = .06) nor to have been published with findings in agreement with the FDA’s interpretation (98% vs 93%; P = .28) (Figure). Subgroup analyses suggest that the changes in overall publication rate were primarily the consequence of publishing negative trials, as all pre-FDAAA and post-FDAAA positive trials were published (72 of 72 and 35 of 35, respectively), whereas 38% (5 of 13) of pre-FDAAA negative trials were published vs 100% (5 of 5) of post-FDAAA negative trials.

Figure. Pre- and Post-FDAAA Efficacy Trials Supporting Neuropsychiatric Drugs First Approved Between 2005 and 2014: Publication Status and Published Conclusion Concordance With FDA Decision

FDA indicates the US Food and Drug Administration; FDAAA, the 2007 Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act.

Conclusions

After FDAAA was enacted, all efficacy trials reviewed by the FDA as part of new drug applications for neuropsychiatric drugs were registered, with the results reported and published. Moreover, nearly all were published with interpretations that agreed with the FDA’s interpretation. While our study was limited by searching for registration status only on ClinicalTrials.gov, our findings suggest that by mitigating selective publication and reporting of clinical trial results, FDAAA improved the availability of evidence for physicians and patients to make informed decisions regarding the care of neuropsychiatric illnesses.

1Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA, constance.zou@yale.edu; 2Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 3McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA; 4Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; 5Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA; 6Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA; 7Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, CT, USA; 8Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA; 9Department of Health Policy and Management, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA; 10Division of Medical Ethics, Department of Population Health, NYU School of Medicine, Bioethics International, New York, NY, USA

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Constance Zou has received a fellowship through the Yale School of Medicine from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Jennifer Miller has received research support through New York University from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to support the Good Pharma Scorecard. Harlan Krumholz and Joseph Ross have received research support through Yale University from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from Medtronic and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for postmarket surveillance of medical devices, and from the US Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting. Harlan Krumholz also has received compensation as a member of the Scientific Advisory Board for United Healthcare. Joseph Ross has received research support through Yale University from the FDA to establish a Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation at Yale University and the Mayo Clinic, from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association to better understand medical technology evaluation, and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to support the Collaboration on Research Integrity and Transparency at Yale University.