Understanding How a Language Model Assesses the Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials: Applying Shapley Additive Explanations to Encoder Transformer Classification Models

Abstract

Fangwen Zhou,1 Muhammad Afzal,2 Rick Parrish,1 Ashirbani Saha,3 R. Brian Haynes,1 Alfonso Iorio,1,4 Cynthia Lokker1

Objective

Deep learning models for classifying published clinical literature to support critical appraisal have garnered wide attention.1 To automate the critical appraisal workflow for McMaster’s Premium Literature Service (PLUS), a gold-standard database manually labeled by experts was used to develop well-performing models to classify the rigor of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).2 However, due to the complexity of language models, the lack of transparency remains an important concern. This study explored Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)3 to better understand how a deep learning model makes classification decisions.

Design

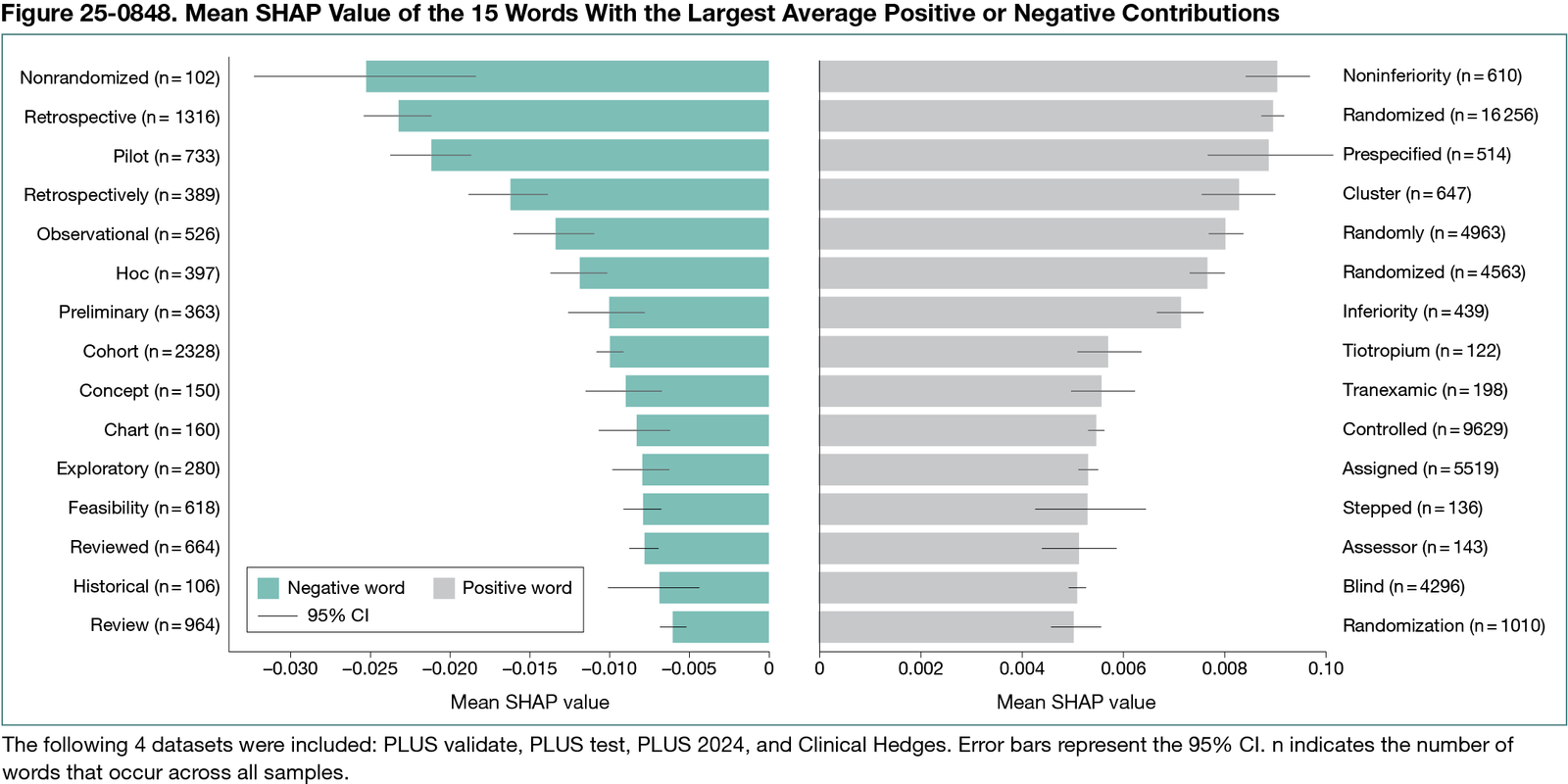

Details regarding the development and evaluation of the rigor classifiers are published elsewhere.2 Briefly, classifiers were trained with titles and abstracts of original RCTs, that met or did not meet PLUS criteria for rigor (randomization, ≥10 participants per group, ≥80% follow-up, clinically important outcomes, and preplanned subgroup analyses, if applicable). Models were trained on 53,219 PLUS articles from 2003 to 2023, randomly split 80:10:10 into train, validate, and test sets. Articles in Clinical Hedges, a similar database that preceded PLUS, and PLUS articles from 2024 were used for external testing. A top-performing BioLinkBERT model, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 94%, was selected for this study. The SHAP partition explainer determined important tokens (words/subwords) for articles from the validate and test datasets, Clinical Hedges, and PLUS 2024. Tokens were combined into words for ease of interpretation, and their SHAP values were summed. The mean SHAP values, which indicate the aggregated average marginal contribution to model output over all samples, for the most impactful words with 100 or more occurrences were examined.

Results

Overall, 6,207,935 words were analyzed, of which 49,387 were unique. Figure 25-0848 shows the 15 most impactful unique words for positive (rigorous) and negative (nonrigorous) classes. Terms such as noninferiority positively influenced rigor predictions with a mean SHAP value of 0.00904 (95% CI, 0.00844-0.00965), whereas nonrandomized (mean SHAP value, −0.02510; 95% CI, −0.03204 to −0.01816) had negative impacts. These results generally align with the manual appraisal criteria. However, tokens apparently unrelated to the criteria, such as tiotropium (mean SHAP value, 0.00571; 95% CI, 0.00508-0.00634), also had sizable impacts, indicating that they may have been correlated with higher rigor during manual appraisal. These patterns were learned and applied by the model, indicating a certain degree of overfitting.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that SHAP helps understand which features influence a deep learning model’s rigor assessment of an RCT. Identifying influential features increases confidence in the model assessments and generalizability and reduces unease about the black-box nature of these models. Future work should explore SHAP with other critical appraisal tools and datasets and potentially integrate it into machine learning systems to improve user trust and model accountability in evidence synthesis and critical appraisal workflows.

References

1. Lokker C, Bagheri E, Abdelkader W, et al. Deep learning to refine the identification of high-quality clinical research articles from the biomedical literature: performance evaluation. J Biomed Inform. 2023;142:104384. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104384

2. Zhou F, Parrish R, Afzal M, et al. Benchmarking domain-specific pretrained language models to identify the best model for methodological rigor in clinical studies. J Biomed Inform. 2025;166:104825. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2025.104825

3. Lundberg S, Lee SI. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv. Preprint posted online May 22, 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874

1Health Information Research Unit, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, lokkerc@mcmaster.ca; 2Faculty of Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK; 3Department of Oncology, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; 4Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

McMaster University, a nonprofit public academic institution, has contracts through the Health Information Research Unit under the supervision of Alfonso Iorio and R. Brian Haynes. These contracts involve professional and commercial publishers to provide newly published studies, which are critically appraised for research methodology and assessed for clinical relevance as part of the McMaster Premium Literature Service (McMaster PLUS). Cynthia Lokker and Rick Parrish receive partial compensation, and R. Brian Haynes is remunerated for supervisory responsibilities and royalties. Ashirbani Saha, Fangwen Zhou, and Muhammad Afzal are not affiliated with McMaster PLUS.

Funding/Support

Fangwen Zhou was funded through the Mitacs Business Strategy Internship grant (IT42947) with matching funds from EBSCO Canada.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funders were not involved in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the abstract, and decision to submit the abstract for presentation.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Digital Research Alliance of Canada for providing the computational resources.