The Influence of Promotional Language on Evaluations of BiomedicalLiterature: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

Neil Millar,1 Brian Budgell2

Objective

Promotional language (hereafter, hype) in scientific writing has increased significantly over the past 40 years.1 Analyses of grant proposals have found the incidence of hype to be positively associated with funding success2; however, evidence of causality is still lacking. Furthermore, an underpowered pilot study suggested that hype may bias clinicians’ perceptions and evaluations of evidence.3 This study tested the hypothesis that students’ appraisal of biomedical research abstracts is influenced by hype.

Design

A double-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted to assess readers’ evaluation of hyped vs nonhyped abstracts. Four structured abstracts were selected from leading spinal care journals, controlling for length and absence of hype. Hyped abstracts were modified to include 6 common hype terms, such as “carefully designed” to highlight methodological rigor, “this is the first study to” to emphasize novelty, “convincing evidence” to amplify results, and “conducted by an experienced radiologist” to emphasize researcher competence. Inclusion criteria were that participants were second-year or higher chiropractic students recruited from institutions in the UK, US, and Canada. A blinded researcher randomly selected folders for students to evaluate. Participants rated abstracts on a 10-point scale, using 4 criteria: implementation likelihood, rigor, novelty, and researcher competence. A linear mixed-effects model was used to assess whether evaluations were influenced by hype, accounting for variability across participants and abstracts.

Results

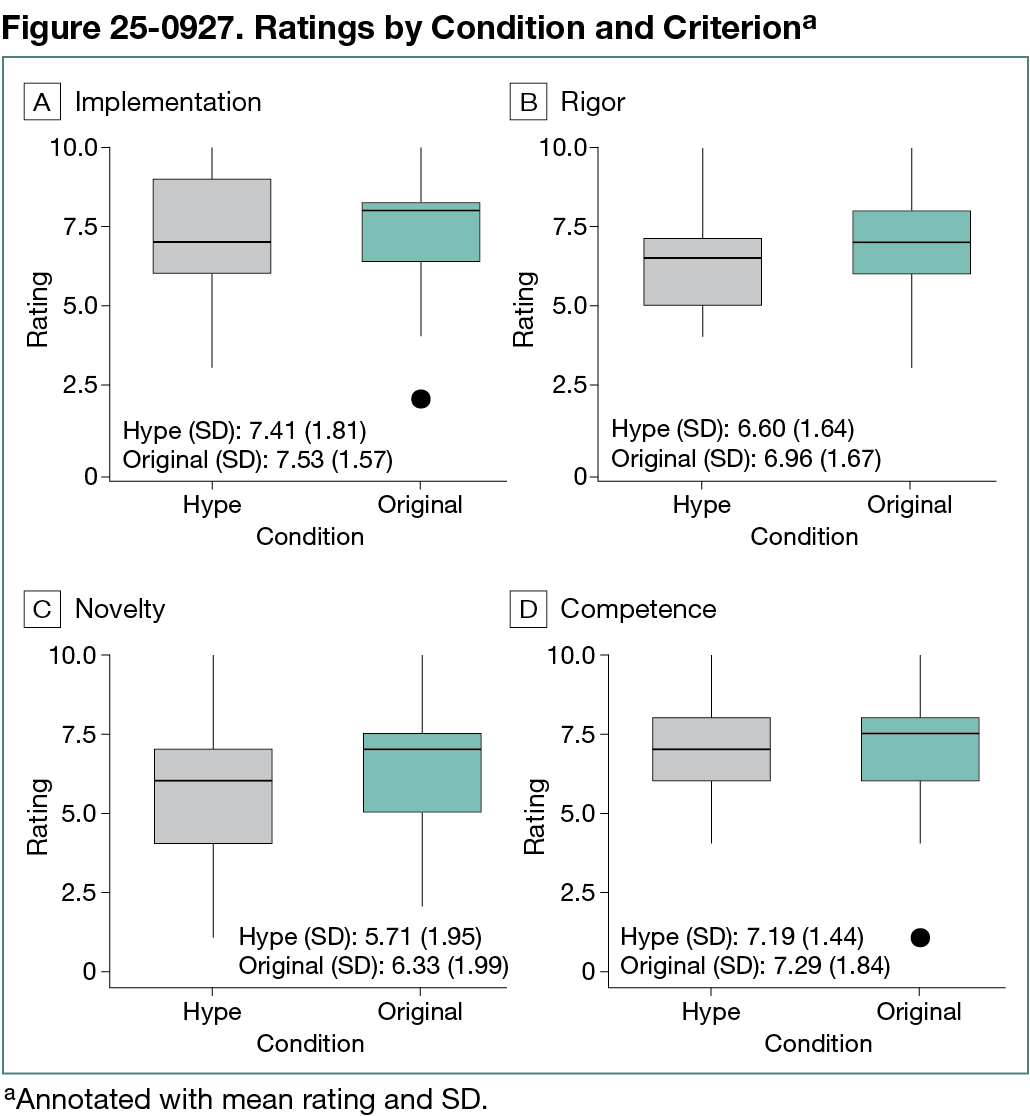

This ongoing study began on April 2, 2024. As of January 2025, 36 students at 3 institutions had completed the rating task. Mixed-effects modeling, including interactions between condition and criterion, showed no significant differences between hyped and original abstracts across all evaluation criteria (estimate, 0.067; P > .05) (Figure 25-0927). While novelty received consistently lower ratings (estimate, −1.479; P < .001), the influence of hype did not vary significantly by criterion, as interaction terms were nonsignificant (eg, condition × novelty interaction [estimate, 0.517; P > .05]), indicating minimal measurable effect of promotional language.

Conclusions

Within this experimental paradigm, hype did not appear to bias readers’ evaluation of the scientific merit of the literature. These findings are discussed in relation to evidence-based medicine and bias on the part of researchers, reviewers, editors, and other stakeholders. Limitations of the study include the small sample size reported to date and restriction of the experimental texts to abstracts.

References

1. Millar N, Batalo B, Budgell B. Trends in the use of promotional language (hype) in National Institutes of Health funding opportunity announcements, 1992-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2243221. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.43221

2. Qiu HS, Peng H, Fosse HB, Woodruff TK, Uzzi B. Use of promotional language in grant applications and grant success. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(12):e2448696. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.48696

3. Millar N, Budgell B. Impact of hype on clinicians’ evaluation of trials—a pilot study. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2023;67(1):38-49.

1Faculty of Engineering, Information and Systems, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan; 2Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, bbudgell@cmcc.ca.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None reported.

Funding/Support

This study was supported by grant 21K02919 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the abstract; and decision to submit the abstract for presentation.