Funding Sources and the Online and Academic Impact of Cardiovascular Trials Published in Highest-Impact Journals

Abstract

Farbod Zahedi Tajrishi,1 Sina Rashedi,2 Ashkan Hashemi,3 Isaac Dreyfus,4 Nicholas Varunok,5 John Burton,6 Seng Chan You,7 Björn Redfors,3,8 Gregory Piazza,2 Joshua D. Wallach,9 Lesley Curtis,10 Sanjay Kaul,11 David J. Cohen,8,12 Roxana Mehran,13 Flavia Geraldes,14 Joseph S. Ross,15 Jane Leopold,2 Harlan M. Krumholz,15 Gregg W. Stone,13 Behnood Bikdeli2,15

Objective

Altmetric scores capture online engagement with research, including social media mentions and news coverage, whereas citation counts represent academic impact. It remains uncertain whether the source of funding for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) correlates with the online and academic impact of RCTs overall and within the subsets that meet or do not meet their prespecified primary outcomes. We hypothesized that privately funded trials, particularly those with positive results, would be cited more often and have higher Altmetric scores than publicly funded trials.

Design

We searched PubMed for cardiovascular RCTs published in JAMA, The Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine between 2014 and 2019. This timeframe was selected to ensure sufficient follow-up for citation accrual and stability of Altmetric activity while capturing contemporary cardiovascular research. Trials were classified by funding source: public (ie, governmental), private (including for-profit industry and nonprofit organizations), or hybrid (with both public and private funding). RCT results were considered positive if they met their primary outcome or at least 1 of their coprimary outcomes and negative if they did not. Altmetric scores were obtained from Altmetric.com, and citation counts from Google Scholar (last accessed February 8, 2025). Both metrics were adjusted for publication year.

Results

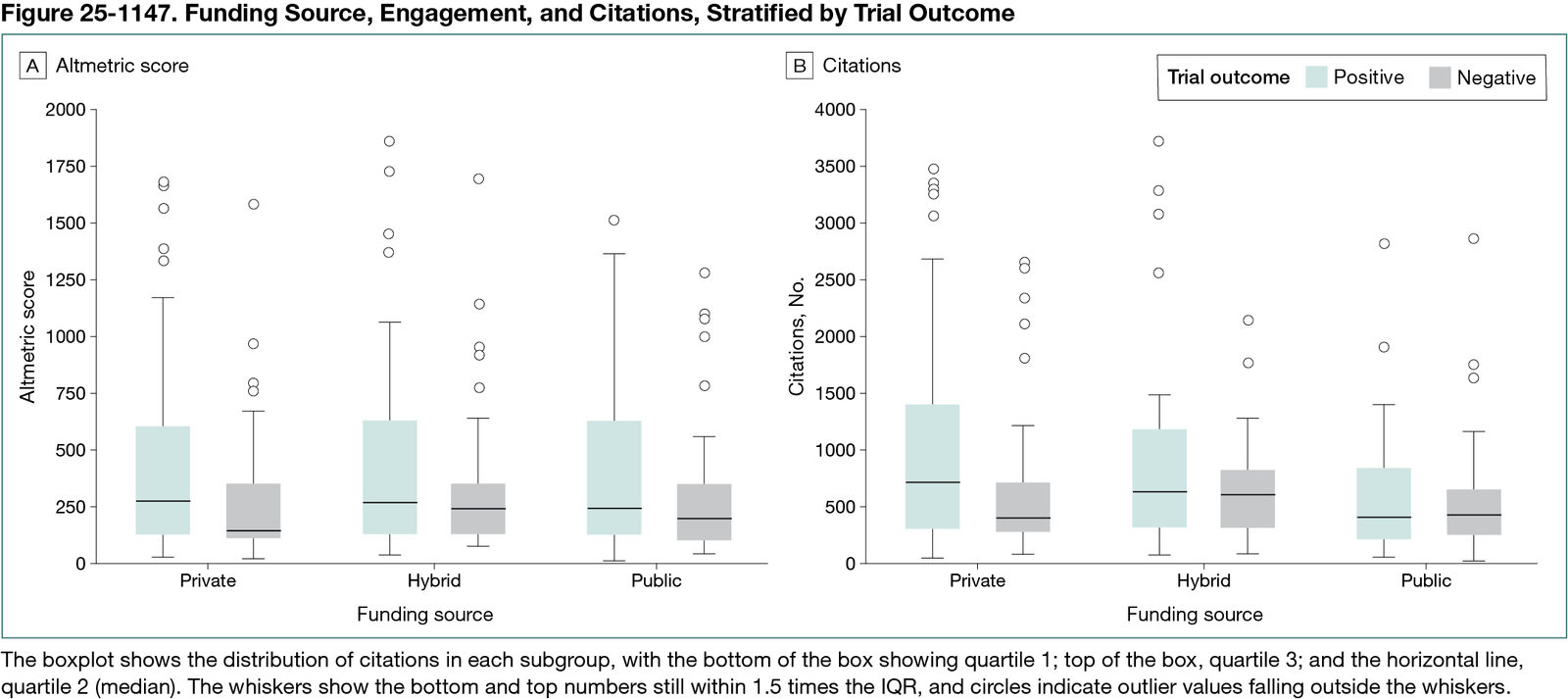

A total of 435 cardiovascular RCTs were analyzed, of which 130 (29.9%) were publicly funded and 197 (45.3%) were privately funded (Figure 25-1147). A total of 175 negative trials (40%) were identified. There was no significant difference across trials for Altmetric score based on the funding source (median [IQR] scores: public, 218.1 [112.3-465.6]; private, 215.1 [112.9-506.6]; and hybrid, 244.5 [127.3-555.8]; P = .49). Publicly funded trials were cited less frequently than privately funded or hybrid-funded trials (median [IQR] citations: public, 410.0 [226.5-724.0]; private, 599.0 [287.0-1022.0]; and hybrid, 607.0 [301.8-936.0]; P = .003). When exploring the findings based on the primary results of the RCTs, median (IQR) citations for positive vs negative publicly funded trials (402.5 [216.3-827.0] vs 419.5 [240.3-644.0] citations) and hybrid trials (614.5 [311.8-1173.3] vs 597.0 [300.5-808.3] citations) were substantively similar, whereas median (IQR) citations for privately funded trials (705.0 [298.5-1395.5] vs 383.0 [262.3-694.8] citations) were higher if they met the primary outcome (P for interaction < .001).

Conclusions

Funding source was associated with subsequent citations, but not the Altmetric score. Publicly funded trials received significantly fewer citations than privately funded trials. Publicly and hybrid-funded trials showed similar citation patterns regardless of outcome, whereas privately funded trials were cited more when the primary outcome was met. These findings highlight the role of funding source in shaping the impact of cardiovascular RCTs.

1Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, US; 2Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, US, bbikdeli@bwh.harvard.edu; 3Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, US; 4David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA, US; 5Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, US; 6Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, CA, US; 7Department of Biomedical Systems Informatics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea; 8Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY, US; 9Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, US; 10Duke University and Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI), Durham, NC, US; 11Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, US; 12St Francis Hospital & Heart Center, Roslyn, NY, US; 13Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, US; 14The Lancet Group, London, UK; 15Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE), Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, US.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None reported.